Ex-slave Mary Prince was a ‘savvy narrator’ who used religion to convince the British public that black people were human beings

“Mary Prince brought a distinctly female voice to the abolition debate at a time when women’s voices were completely obscured”

When The History of Mary Prince, the first account of a black woman’s life in Britain, was published in 1831 it scandalised the British public, galvanised the anti-slavery movement and contributed to the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833.

But who was Mary Prince, slavery’s everywoman whose revelations about the reality of life as a female slave spoke for millions of silent women? And how did she get the British public not just to listen to her story but to care?

A new book titled Protestant Empires: Globalizing the Reformations edited by Professor Ulinka Rublack, Fellow of St John’s College, University of Cambridge, explores the relationship between religion and slavery. The book brings together leading scholars to discuss global Protestant experiences created by the Reformation in the early modern world.

“Readers did not meet a helpless female victim, they met a woman who protested mistreatment, disobeyed orders, defended herself”

In a chapter dedicated to Prince, Professor Jon Sensbach, a historian at the University of Florida, determines that at the heart of The History of Mary Prince is a passion story rooted in sacrifice and redemption.

He examines the role of spirituality in the life of Prince, who was born a slave in Bermuda and was sold from one brutal owner to another before arriving in London in 1828 where she was suddenly a free woman because The Act of Parliament to abolish the British slave trade had passed in 1807.

After months of working as a servant for John Wood, a sadistic white man from London who bought her in Antigua and brought her to England, Mary Prince ran away to a missionary group which directed her to the Anti-Slavery Society.

Abolitionists quickly spotted the public relations value of her story and the poet Susanna Strickland was used as a ghostwriter for The History of Mary Prince. Although Prince could read it is not clear whether she could write.

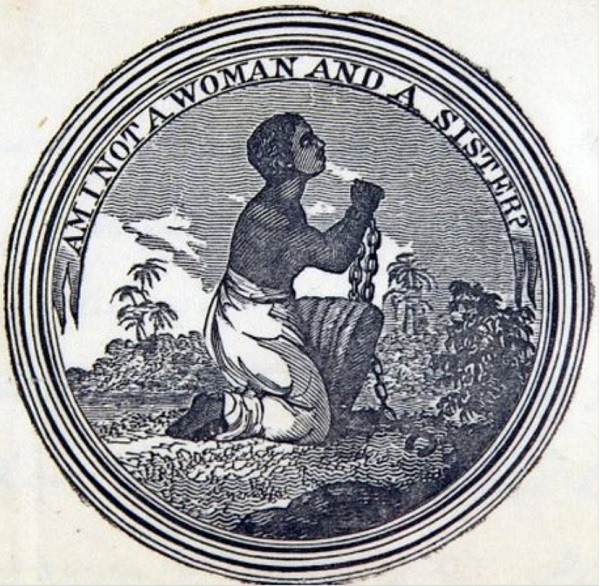

Professor Sensbach said: “Mary Prince brought a distinctly female voice to the abolition debate at a time when women’s voices were completely obscured. Readers did not meet a helpless female victim, they met a woman who protested mistreatment, disobeyed orders, defended herself and ultimately emancipated herself.

“This highly scripted account was the first time that enslaved women were at the forefront of the anti-slavery campaign and when The History of Mary Prince was published, British slaveholders and their defenders vehemently attacked her character and attempted to discredit her.”

It is widely accepted that The History of Mary Prince was heavily edited to suit the abolitionist cause – a campaign was still being waged in an attempt to outlaw slavery throughout the British Colonies. Prince soon realised that although she was free by law in London, if she managed to return to her beloved husband in Antigua she would be enslaved again.

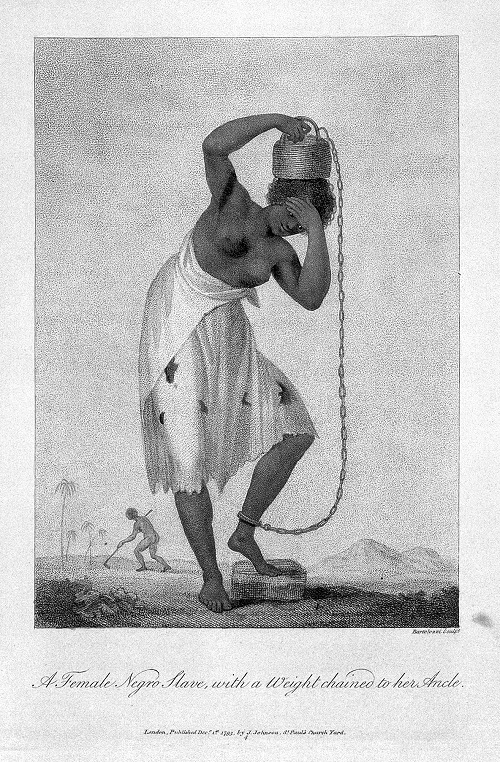

The History tells how Prince’s life was a merry-go-round of being exchanged ‘from one butcher to another’ across the Caribbean Islands. Her graphic account of being sold at a market by her devastated mother included a description of how she was ‘soon surrounded by strange men, who examined and handled me in the same manner that a butcher would a calf or a lamb he was about to purchase’.

“Mary Prince played on the emotions of the British public to make slaves be seen as human beings who felt and suffered just like they did”

She met Daniel James, a free carpenter, through the Moravian Church in Antigua and married him without permission. She was whipped for her lack of obedience, beaten and imprisoned. The History tells the shocked British people about what went on in the British Colonies in their name and even carefully alludes to the sexual abuse of slaves.

Professor Sensbach, who travelled to the Caribbean to comb through the archives of the Moravian Church and the missionaries, said: “Mary Prince detailed the violence against women – the scarring of their bodies, the scarring of their souls - and she played on the emotions of the British reading public to make slaves, and specifically female slaves, be seen as human beings who felt and suffered just like they did. “Prince explained, in very graphic terms, what it was like to be beaten to a pulp and referred obliquely to the rape of women. She said the worst thing about being a slave was not being whipped or the pain of the boils caused by standing in saltwater for days on end, but being exposed to the ‘indecency’ of masters. ‘Worse to me than all the licks’ was being forced to see one of these men naked while she bathed them. The metaphoric violence of immodesty stands for the violence of rape.”

“Mary Prince uses religion as a crucial weapon in the fight for freedom by taking the moral authority”

He says Prince knew that explicitly detailing the sexual violence meted out to her would negatively influence public opinion of her – female slaves were considered to be ungrateful promiscuous jezebels who brought sexual attention on themselves.

Professor Sensbach said that instead Prince was a ‘savvy narrator’ who carefully positioned herself as a ‘suffering servant of God’ and portrayed her conversion to Christianity as an essential milestone on the path to physical and spiritual freedom.

He explained: “The fusion of religion and anti-slavery in The History is so important because it gives us a firsthand account of women’s spiritual lives. Religion was used to control slaves around the world and enslaved women were often very powerful leaders who spread the messages of Christianity. Mary Prince herself uses religion as a crucial weapon in the fight for freedom by taking the moral authority and showing the battle between not just slavery and freedom but between belief in God and disbelief.”

Professor Sensbach details Prince’s adoption of Christianity and her membership of the Moravian Church – which was very pro-slavery - in Antigua and how it intersects with her African roots and influences.

He said: “Prince describes how God intervenes to save her from death after her friend is beaten to death by her master and says ‘the hand of God mercifully preserved me for better things’. She makes religious slaves appear as the righteous and the slave-owners as blasphemous tyrants. The depiction of Mary Prince as a suffering servant not only of God but of slave-owners, is the ethical bedrock of her story.”

Professor Rublack, a Reformation Historian, added: “This chapter in the book is particularly poignant as it tells us how Mary Prince had to silence her indigenous Afro-Caribbean spirituality to conform to the narrative that would ‘play’ best with the British public. It means we have lost the mixture of different traditions and what they could bring to faith and to the spiritual lives of enslaved people. Our book examines how Moravians dished out constant discipline to slaves in the colonies to keep them compliant and how enslaved women gained leadership roles in the Church. But the price to pay was that female slaves also became part of a system that oppressed and punished slaves.”

It is not known exactly when or how Mary Prince died and no images of her exist, but Professor Sensbach reveals in the book that towards the end of her life she was rejected by her church in London and was not allowed to worship there because she was considered to be a ‘sexually promiscuous sinner’.

He said: “The Moravian Church in London turns its back on Mary Prince and renounces her and she dies in very mysterious circumstances. We don’t even know if she lived to see slavery abolished in the colonies so her whole life was a narrative of martyrdom and sacrifice on behalf of a bigger cause.”

- Protestant Empires: Globalizing the Reformations edited by Professor Ulinka Rublack, Fellow of St John’s College, University of Cambridge, and published by Cambridge University Press, is out now.

Published: 1/10/2020